Our next High Day will be a Samhain Norse Blot to The Ancestors High Rite on 1 November 2025.

What we celebrate

The word “Yule,” according to Bede and various other authorities of the olden time is derived from an archaic Norse word “Jol,” meaning “a wheel.”

Solstice celebrations are universal & perhaps much older than we know. Many, many cultures the world over perform solstice ceremonies. At their root was an ancient fear that the failing light would never return unless humans intervened with anxious vigil or antic celebration. Solstice celebration are documented from around the world, from ancient Egypt to modern day Kwanzaa celebrations.

The Winter Solstice represents the rebirth of the sun, which is a particularly important turning point. The night of Solstice is the longest night of the year. Darkness triumphs and yet it gives way and changes into light. Yule is the time when we honor the Goddess for giving birth to the sun once more.

Yule is a time when we do Rituals and celebrate the increasing daylight, to renew, and to see the world through the eyes of a child. Spells done at Yule tend to raise our spirits, and bring harmony, peace, and joy. During Yule we see the wisdom of past experience begin to glimmer. The experiences we yielded over the harvest season of the times gone past begin to be reborn as wisdom, new light, to guide us further down the Paths we have chosen.

It is customary to decorate the Yule tree, and adorn the house with holly, ivy and pine. It is time when Father Winter, a white bearded chap dressed in red fur- trimmed robes arrives bearing gifts.

This is the eve when the Yule log from the previous year is burned in the fire. Symbolic of the newborn sun, each year’s Yule log is of oak, charged in ritual and kept until the following Yule. This not only celebrates the oak and places it in a place of distinguished honor, but also ensures there will be fuel for the remainder of Winter.

Imbolc means ‘in the belly’, im – within, bolc – belly, but has many variant names. Another possible source for the name is from the Irish ‘imb fholc’, washing oneself. This could result from the purification aspects of the holiday. The Irish called it Óimelc, meaning ‘ewe’s milk’ (oi – sheep, melc – milk).

In most parts of the British Isles, February is a harsh and bitter month. In old Scotland, the month fell in the middle of the period known as Faoilleach, the Wolf-month; it was also known as a’ marbh mhiòs, the Dead-month. But although this season was so cold and drear, small but sturdy signs of new life began to appear: Lambs were born and soft rain brought new grass. Ravens begin to build their nests and larks were said to sing with a clearer voice.

In Ireland, the land was prepared to receive the new seed with spade and plough; calves were born, and fishermen looked eagerly for the end of winter storms and rough seas to launch their boats again. In Scotland, the Old Woman of winter, the Cailleach, is reborn as Bride, Young Maiden of Spring, fragile yet growing stronger each day as the sun rekindles its fire, turning scarcity into abundance.

At Imbolg, we, like all of nature, await the coming of spring, the Vernal Equinox, when day and night are equal, which tells us that the light has vanquished the dark and a change is upon the land.

The name for this Sabbat actually comes from that of the Teutonic lunar Goddess, Eostre. Symbols used to represent Ostara include the egg (for fertility and reproduction) and the hare (for rebirth and resurrection), the New Moon, butterflies and cocoons.

Ostara is a time to celebrate the arrival of Spring, the renewal and rebirth of Nature herself, and the coming lushness of Summer. It is at this time when light and darkness are in balance, yet the light is growing stronger by the day. The forces of masculine and feminine energy, yin and yang, are also in balance at this time.

Ostara is a time for renewal, when we should reaffirm our commitment to those things that are important to us and revitalize our journey towards our goals. It’s a time to play silly games and to let go of the darkness of winter and welcome the light of spring into our hearts.

Symbolically, many Pagans choose to represent Ostara by the planting of seeds, potted plants, ringing bells, lighting new fires at sunrise, either in the fireplace (if the weather us still cold enough), in the the cauldron, or light a balefire (if outdoors).

Beltane is said to mean anything from “Bale-fire” to “bright fire.” Beltane is a festival of flowers, fertility, sensuality, and delight. It celebrates the height of Spring and the flowering of life. Most crops are planted by Beltane, allowing farmers a chance to take a break after the busy spring.

People would celebrate with huge bonfires. Once the fire had been kindled, people danced sun wise round it and jumped through the flames. As the fire was dying down, the animals that had wintered over in barns and local pastures were driven, on their way up to the summer grazing, between the parted fire to ensure their fertility. Before the coals died out, people took fire from the ceremonial blaze to rekindle their hearths (which had been extinguished in every household prior to the festival). A May Queen and King would be chosen- usually the lustiest of the young people- to represent the Gods.

The explosion of May-blossom, sunlight, and burgeoning life needs expression at this time, when workday commonplaces can be thrown to the four winds and the bright joy of living can bubble up within us with natural ecstasy. All who have waited at dawn to welcome in summer have felt the sudden burst of brightness that ignites the deep happiness of the living earth as the sun rises.

In modern Celtic traditions, it has become the traditional time for handfasting (Pagan marriage rites). This comes from the sabbat’s main purpose: the celebration of the sexual union or marriage of the Goddess and God.

As everything in nature comes to its peak and then declines, so too must the God in His aspect of the Sun. But with decline comes transformation, and so it is with the God, who takes on many aspects and wears many crowns.

Like Samhain, Litha (The word ‘Litha’ is linguistically related to the Germanic or Norse word for Light or Month, depending on the tribe and dialect.) is a day when the boundaries between the worlds are thin, when mortals have strange experiences, and when faeries troop across the land. Litha is a “day outside of time,” and the strange experiences one might have are likely to be comic, harmless, or even beneficial. Litha has an “upside down” quality about it – things are often reversed or mixed-up.

This is the longest day of the year, and one where the veils are once more thin between the realms of the Sidhe (the Faerie realm) and the world of mortals. It is a time for merriment and the making of wishes. .

In nearly every culture, the Summer Solstice has been recognized, revered and even feared. The Sun is at its height, but at the same moment begins to decline. Only hope, ritual and belief would ensure its return at the Winter Solstice. To early peoples, this must have seemed an amazing and awe-inspiring event. To us modern Witches, it still is.

Litha is about joy. It is about being completely alive, as the earth is at its zenith. Everywhere you look, it’s green. Weave flowers into your hair – dance and frolic, take a big, deep cleansing breath of summer air. Bake fresh bread and let the smell fill your house. Realize that you are special and have a purpose. We are the Goddess’s children and the Earth is our home.

Lughnasadh is named for Lugh, the Celtic deity who presides over the arts and sciences. According to Celtic legend, Lugh decreed that a commemorative feast be held each year at the beginning of the harvest season to honor his foster mother, Tailtiu. Tailtiu was the royal Lady of the Fir Bolg. After the defeat of her people by the Tuatha De Dannan, she was obliged by them to clear a vast forest for the purpose of planting grain. She died of exhaustion in the attempt. The legend states that she was buried beneath a great mound named for her, at the spot where the first feast of Lughnasadh was held in Ireland, the hill of Tailte. At this gathering were held games and contests of skill as well as a great feast made up of the first fruits of the summer harvest.

Games and contests in honor of the dead were an ancient tradition across Europe. Offering up a portion of the harvest to the Gods and the Ancestors and feasting in their honor was also a common tradition in Europe and in indigenous cultures throughout the world.

The name of Lugh is derived from the old Celtic word “lugio”, meaning “an oath”. A traditional part of the celebrations surrounding Lughnasadh have been the formation of oaths. From before recorded history into the twentieth century marriages, employment contracts and other bargains of a mundane nature were formed and renewed at this time of year. Since the agricultural year had its culmination in the harvest and the harvest festivals, oaths and contracts that had to wait until after the crops were in could be focused on at this time. Marriages, hiring for the upcoming season and financial arrangements were often a part of the Lughnasadh activities and in many areas fairs were held specifically for the purpose of hiring or matchmaking.One common feature of the Games were the “Tailltean marriages”, a rather informal marriage that lasted for only “a year and a day” or until next Lammas. At that time, the couple could decide to continue the arrangement if it pleased them, or to stand back to back and walk away from one another, thus bringing the Tailltean marriage to a formal close. Such trial marriages were quite common even into the 1500’s, although it was something one “didn’t bother the parish priest about”.

During this time, you may choose to do volunteer work for the less fortunate to express your thanks for the blessings in your life. This also a good time to banish fears.

The name Mabon comes from the Welsh God Mabon ap Modron,(the “great son of the great mother”), also known as the Son of Light, the Young Son, or Divine Youth. The Equinox is also the birth of Mabon, from his mother Modron, the Guardian of the Outerworld, the Healer, the Protector, the Earth.

At this time of balance, of suspended activity, the veil between the worlds is thin. This Sabbat is symbolized by the double spiral, a going-in and a returning, to remind us, as we begin the journey inwards towards the darkest point of the year, that death is always followed by rebirth, just as winter is always followed by summer. “Whatsoever rises must also set, and whatsoever sets must also rise”

Lastly, it is a time of reflection, of gathering in completed projects, of sorting the good from the worn and choosing the seeds for next year’s planting. It is a time to reflect on, and give thanks for, the achievements of the year. Now, though, we must also let go, with thanks, of things which have had their time and are slipping away, and cast away anything that we no longer need, or that is holding us back from achieving that which we wish to “plant”‘ in the coming year. We are reminded that all things have their seasons, and that just as summer was temporary, so too is the coming winter.

A feast for friends and family always provides a cheerful abundance of energy and thanks during this time. Additional seeds and grains can be set out as offering to our fellow creatures, and provide a healthy chance for birds to join in the celebrations as well. Symbolic designs can be made out of the sprinklings if one chooses. Those less fortunate should not be omitted from the celebration. This is an excellent time to donate food gifts to the needy. To honor the dead, it is traditional to place apples on burial cairns as symbolism of rebirth and gratitude. But above all, it is a time to honor the elders and ancestors, who have devoted so much time and energy to our growth and development. Something special is in order for these gracious people.

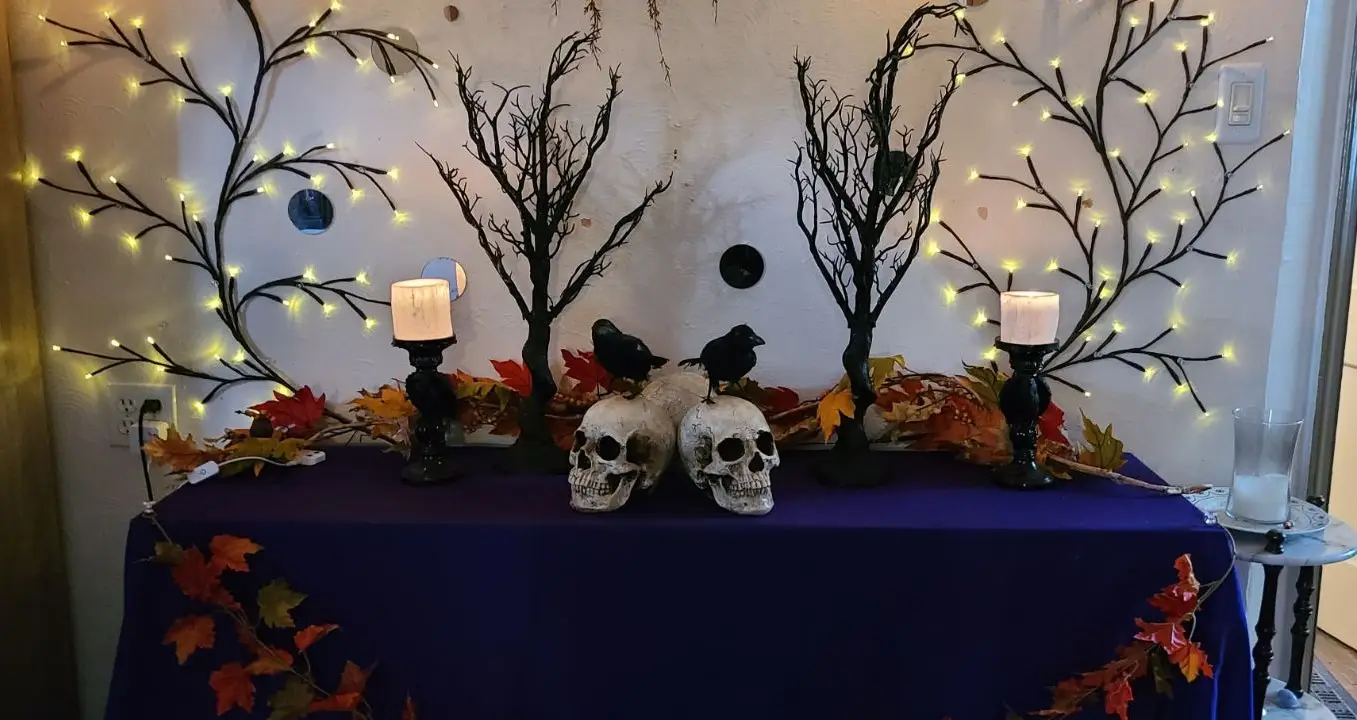

The Festival of Samhain marks the ending and beginning of the Celtic Year. Samhain (pronounced “Sow-in”) comes from the Irish Gaelic and means “Summers End”.

First, it was an important agricultural observance, when the final harvest was taken and the folk were now dependent on stored food, hunting and slaughtering of animals for survival. Herds were culled to eliminate the weak and unnecessary and ensure that the limited amount of food would go around for the next six months. In this aspect, Samhain is a holiday of Plenty and feasting, laying in a layer of fat before the winter, and gathering together for safety and protection.

Samhain is also a time when the veil separating our world, the mortal realm, and the world of the Gods and spirits becomes thin. As such, it is a good time to commune with the recently departed before they continue their journey from death to the “Summerland” –

the realm of the Gods. There they can enjoy an eternal paradise of feasting, joy and plenty, until they are ready to cross back over to our realm and become incarnate beings again.

Likewise, the separation between past, present and future becomes blurred, allowing for glimpses not only into the realm of the ever Young, but of things which have not yet come to pass. Divination has been historically popular at Samhain, from the Irish myths; to children casting nuts into a fire and kenning their future sweetheart by the way they pop and burn.

Samhain is the time when we connect with the vital forces of nature and make ourselves ready for the long descent into winter. It is a time to reflect on that which we’ve brought into our lives, and that which we need for the times to come. Connecting with our roots and examining the directions we need to grow. We feast with the ancestors and ensure the continuing vitality of our people, be it ourselves, our family or the community in which we dwell.

Location

5918 Edna Avenue, Apt A. Baltimore, MD 21214

(please read our parking guidelines)